The face, likely the first aspect one notices about a stranger, determines the opinions and actions made in their direction. Does this random person seem trustworthy? Attractive? Both?

And how do people form these judgments? A new study led by Yi-Fei (Jerry) Hu explores this question. Hu, a PhD student in the Brown University Department of Cognitive and Psychological Sciences, worked with Joseph Heffner (a former CoPsy graduate student and current postdoc at Yale University), Apoorva Bhandari, and Oriel FeldmanHall in a collaboration between the CoPsy Department and the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown University.

In a series of experiments, Hu and his team studied the role of goals in participants’ encoding of social information and making judgements about strangers.

As Hu synthesized, “When you are given a goal, are you able to extract only relevant social information from faces? Are [you] able to filter out irrelevant information?”

Hu and his team uncovered that when assigned a goal, people can filter out their opinions on the attractiveness of a “person” (an artificial face model) to analyze the “person’s” trustworthiness. But they cannot do the reverse, Hu revealed, and perceive trustworthy faces as inherently more attractive. Furthermore, without goal assignment, these two factors inherently intertwine for participants. Social cognition is flexible, Hu explained, so one’s ability to filter relies on what impressions they need to make.

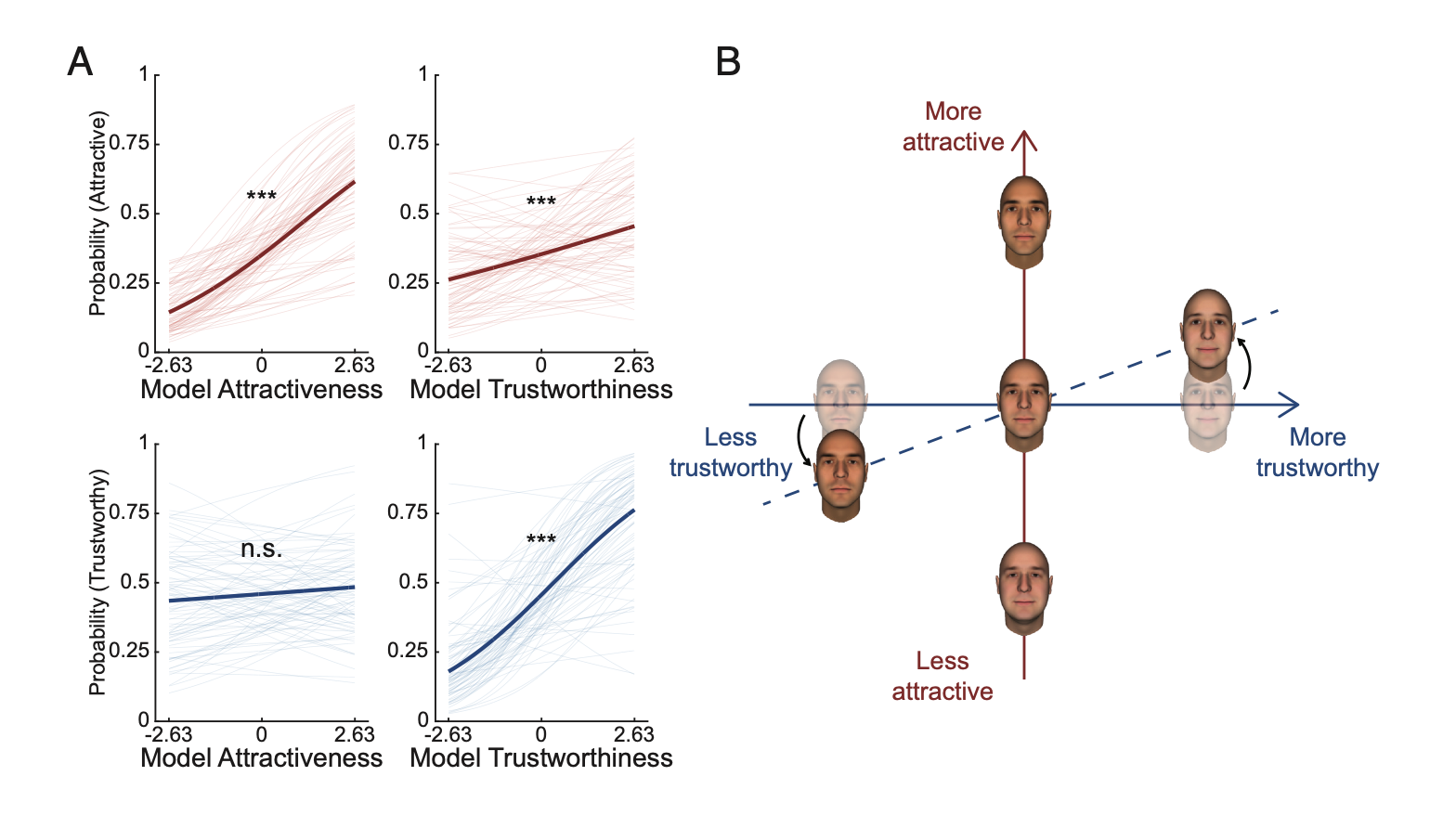

Informed by two existing computational face models that correlate facial features (eye size, for example) and observed social attributes (attractiveness and trustworthiness), Hu, Heffner, Bhandari, and FeldmanHall sought to build a model “that disentangles attractive and trustworthy information in faces,” Hu said. This model then allows them to “freely manipulate either the perceived attractiveness and trustworthiness of faces while holding the other attribute constant.” They had human participants rate faces generated by the model to verify its validity, thereby ensuring its effectiveness.

From there, the team had human participants make judgements about a series of faces generated by the model to have varying perceived attractiveness and trustworthiness. They found that when participants were instructed to judge trustworthiness before seeing the face, they could decipher attractive and trustworthy information, using only the latter to decide. The same, however, was not true in reverse. When told to use attractiveness, people inevitably utilized trustworthy information. The more trustworthy faces were considered more attractive, even though the faces all had the same level of attractiveness.

Furthermore, Hu detailed, when people are not assigned a certain way of approaching a face, they combine the two attributes, considering more attractive faces to be more trustworthy and more trustworthy faces to be more attractive.

These experiments suggest the existence of a trustworthiness “halo effect,” a cognitive bias where a positive characteristic of one kind then influences the person’s perception of another characteristic (in this case, trustworthiness influencing attractiveness). Interestingly, the halo effect is typically associated with physical attractiveness influencing public perception (particularly associations of morality, competence, electability), Hu contextualized. This subversion of the “halo effect” has future implications for analysis of social interaction.

To summarize, Hu and his team found that people seek to fulfill goals based on social attributes but that without prompting, the attributes tend to connect.

This work is supported by the Carney Innovation Grant from the Robert J. and Nancy D. Carney Institute for Brain Science (Oriel FeldmanHall) and the National Science Foundation award 2123469 (Oriel FeldmanHall and Apoorva Bhandari).